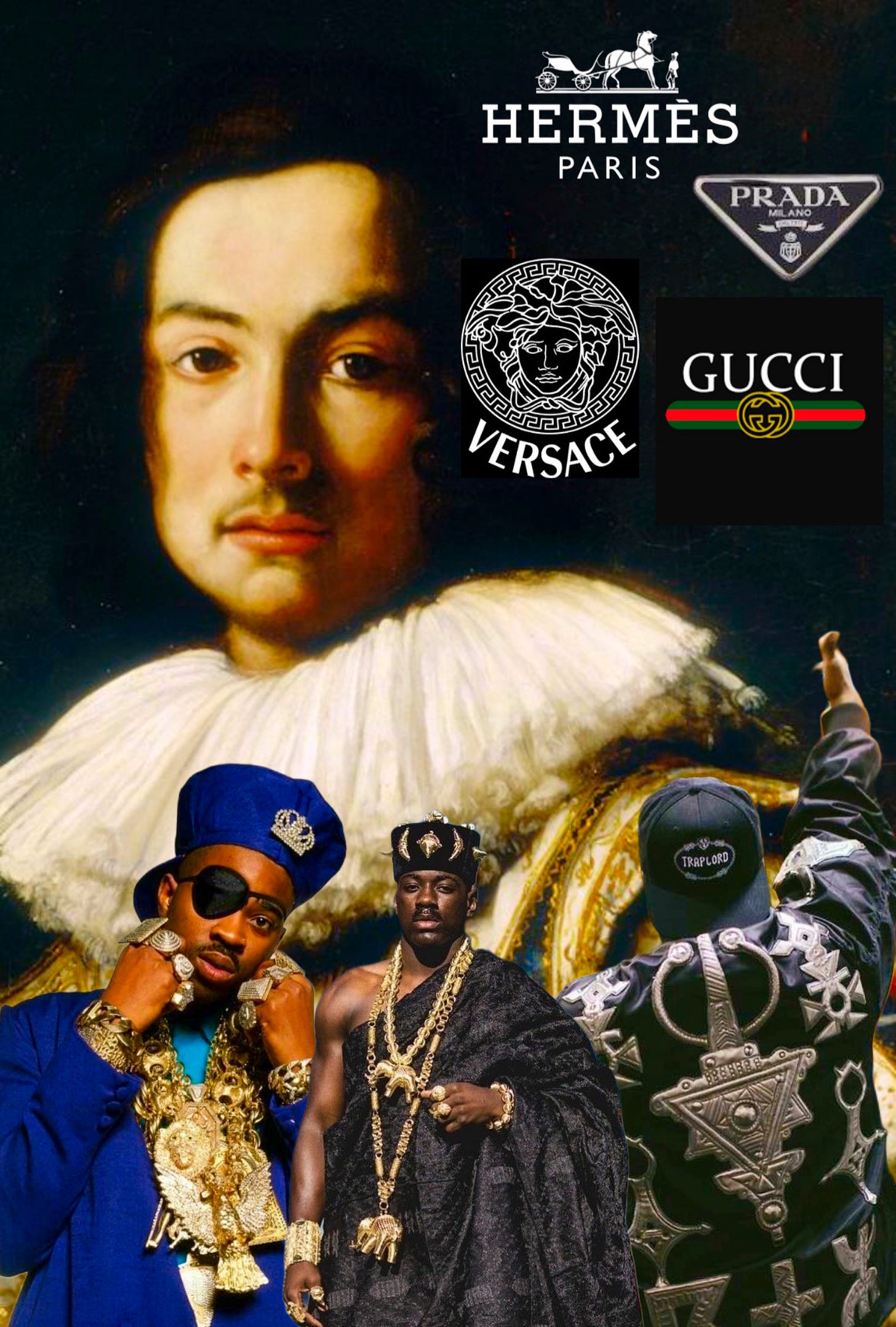

The Politics of Fashion & The Economy of Self-Expression

A comparative look at Renaissance Italy, Medieval West Africa's Gold Coast, and 1990s New York City.

Fashion and Masculinity in Renaissance Italy by Elizabeth Currie is an interesting book exploring how powerful men in Florence, Italy went about flaunting their social dominance through the art of fashion.

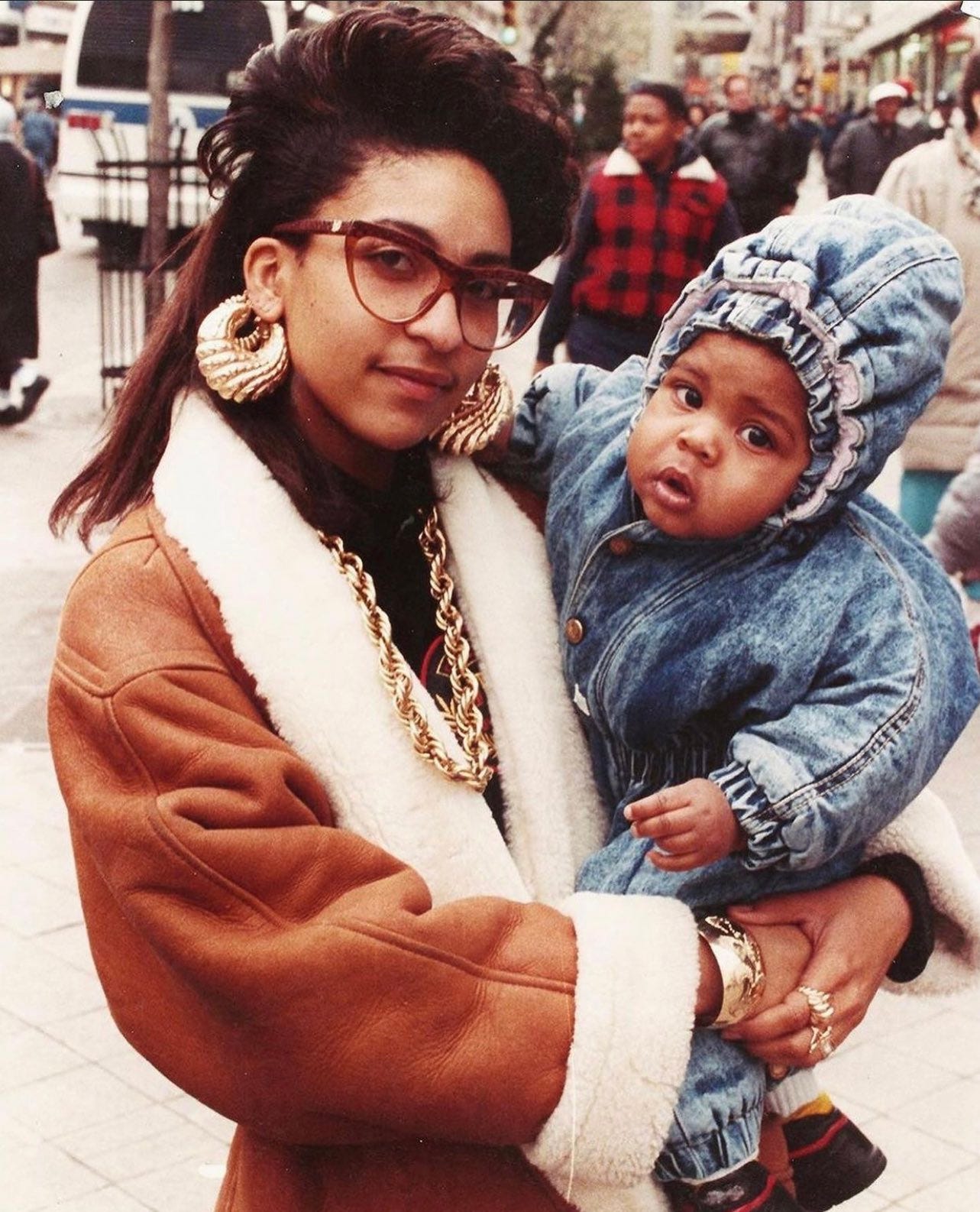

As a Black man from New York City who came of age in the 1990s when French and Italian luxury clothing brands were culturally dominant, I can relate to this social dynamic. I recall similar, yet very unique, power politics dominating the social interactions of my teenage years.

How you dressed in 1990s New York City determined how you were perceived and ultimately how you were treated by others. If you knew how to get fresh, and were well groomed, it signaled to young women that you were socially refined and culturally astute enough for dating.

If you were a young man who couldn’t dress well, didn’t smell good, and constantly looked dusty, it signaled a lack of self-awareness, because why else would you choose to look like a circus hobo? Young women often avoided these guys for practical reasons. A lack of self awareness could be a symptom of mental instability that could potentially pose a threat to women’s safety and well being. The young man with the dirty Reeboks and cheap shirt with faded colors may have rotting human body parts in his bookbag.

The distinguished young lady had better take her chances with the coke peddler pulling up in the new 1994 Lexus GS.

Even during the trade of enslaved Africans hundreds of years ago, clothing provided the wearer with a higher level of security and protection against slave traders trying to take their freedom for the sake of capitalism. In West Africa, cloths imported from Europe were accepted as alternative currencies going as far back as the 1600s, maybe earlier. The cloth was one of the crypto currencies of medieval Africa which fed the modern global economy through the trade of human and material resources.

The exoticism of foreign fabrics fed the local clothing industries along the Gold Coast. The more elaborately you were dressed, the less likely you were to be captured by roving slave traders. The European human traffickers assumed that you were a member of the royal courts that they forged relationships with for trade.

The European explorers only saw Africa as a resource rich hub that they could generate long-term wealth from. That’s why they named regions the “Slave Coast” the “Ivory Coast” or the “Gold Coast” on their maps. All of these slaves, ivory and gold are all commodities that can be bought in bulk and sold at a higher price.

When the Portuguese explorer Diogo de Azambuja met King Kwamina Ansa of Ghana in 1481, the European was amazed by the Ghanaian king’s royal swag and exquisite regalia. The following year in 1482 Christopher Columbus came to Ghana looking for gold. That was 10 years before Spain financed his trip to the Caribbean in 1492.

In the immediate centuries that followed you were less likely to have to petition captors who were looking to enslave you if you got fly. Your drip advocated for your freedom. Poor West African farmers had nothing of tangible distinction to speak for them. Many ended up on the bruise cruises across the Atlantic.

Until the rise of GMO agriculture in the 21st century, it was uncommon to see the descendants of enslaved Africans in urban North America express an interest in old world agriculture. You see the respect for wholistic farmers all over Instagram and TikTok today.

This is in stark contrast to Northeastern American Blacks of the Industrial Revolution who looked down on their relatives in the rural south who tended to the land. Through denationalization propaganda, the land was made to appear synonymous with economic suicide even though it was actually a source of economic power for the natural family unit. We’ll table that for another conversation on another day.

If you are a Black man who knows what it feels like to walk around a department store without evoking criminal suspicion in 2025, you are probably well aware of the cultural intersection between fashion, shallow respectability politics, and racism. The older I’ve gotten, the better I dress, which has translated into more overt gestures of respect from strangers of all walks of life. If I dressed poorly, I would have a poorer experience.

When I was a teenager in Flatbush, Brooklyn, if you wore something that looked amazing, and your peers had a clue where you got it, it gave you an aura of other worldly power without you having to speak or do something. Common human psychology dictates that if you always have to vocally declare your power to others, then the truth is that you don’t have any. People should look at you and immediately see your power on sight. Clothes designed with a passionate spirit of artistry are tangible auric fields that people respond to voluntarily and involuntarily. Respect to all the fashion designers getting folks right.

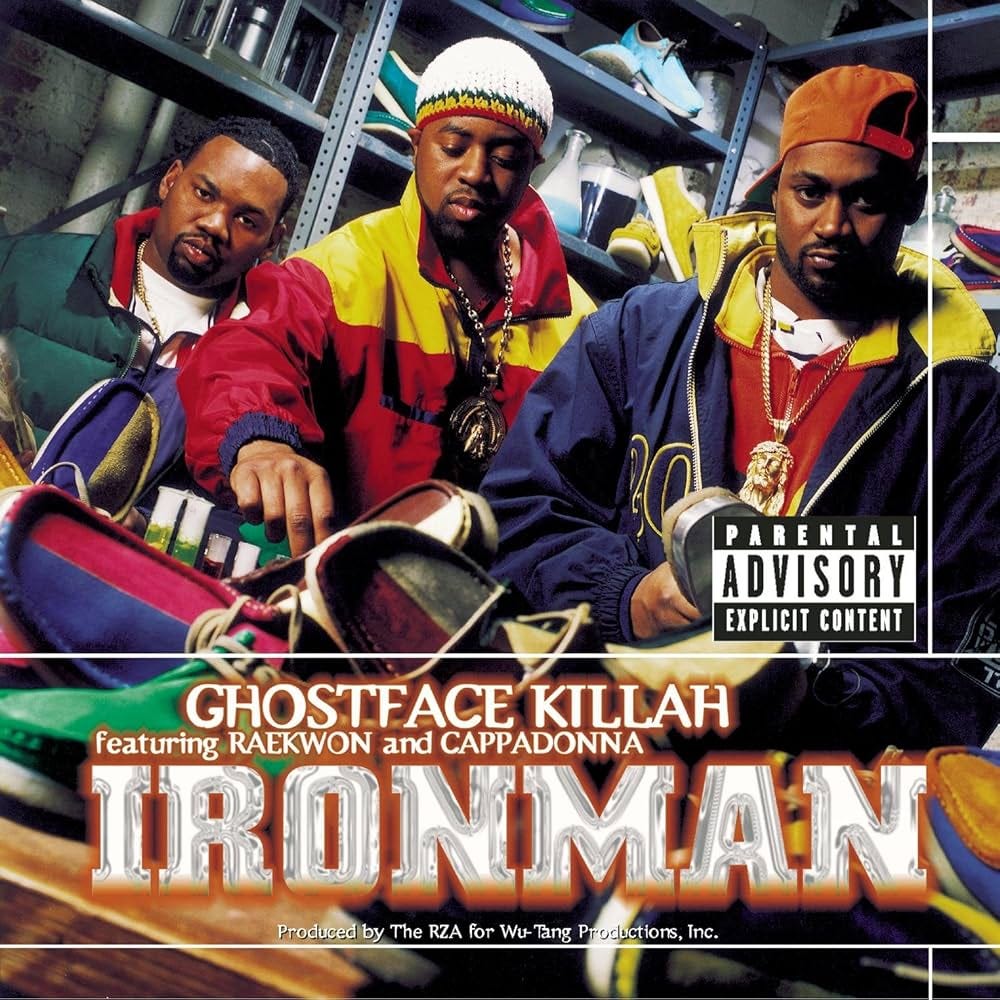

The scarce ACCESS to outlets for creative self-expression for young Black men during the 80s and 90s made how we dressed all the more important and personal to us. The hip-hop music of the time only magnified this culture with constant references to luxury fashion brands from Europe. Tommy Hilfiger and Polo get honorable mentions as respected American brands.

There was no social media, Substack, YouTube, or podcasting platforms in the 1990s, so unless you were super rich and famous, or were a radio show host, you had no means to tell strangers who you were as an individual outside of your fashion. Your clothes helped people to decide whether they wanted to know you beyond what they perceived about you through your immediate appearance.

Up until the COVID pandemic, it was very common in Black American culture, for people to crack jokes about you if you came outside with a bad haircut, hairdo, or wack clothes on. Men and women took pride in looking their best because if they didn’t take pride in their appearance, they would get embarrassed.

There’s an interesting anecdote on the Moor, Alessandro de Medici, in Fashion and Masculinity’s introduction where it describes his penchant for high fashion.

It also highlights Northern Italians criticizing the “ostentatious” styles of dress of Southern Italians. They scoffed at Southern Italian men wearing baggy and oversized clothing that would be more befitting of a larger man. They also talked about how Southern Italians are quicker to spend their money on jewelry and other adornments than they are to be practical and buy elegant furnishings for their homes.

This sounds like the average young Black male in 1997. However, Southern Italy’s proximity to Africa connects a lot of dots for those who consider geography and European history.

This post is not so much a book review. It’s more so a reminder of how fashion impacts human experience across diverse cultures and timelines.

I thoroughly enjoyed this article! The historical and psychological connections between our ancestors survival mechanisms and how they became subconscious behaviors on how we view fashion and status today makes a lot of sense.